Uncovering the mechanics of The Games: Winter Challenge

I’ve recently rediscovered an old game called “The Games: Winter Challenge”, a Winter Olympics sports game developed by MindSpan and published by Accolade in 1991 for DOS and Sega Genesis. I had the DOS version of the game when growing up, so when I was randomly reminded of its existence, I was driven by a mix of nostalgia and curiosity to dig it up again.

Having grown up to become a computer scientist, I was not as much interested in replaying it (though hearing the iconic music again was fun), but much more how it worked under the hood. I had spent hours as a kid playing especially the ski jumping event, trying to reach the elusive mark of 100 meters, without success, and was determined to find out not only whether it was possible to achieve, but also what the theoretical optimum would be. Conveniently, the game features a replay system that allows you to save and rewatch past attempts, which opens up great opportunities for creating a TAS and manufacture a perfect replay file, and push the game to its limits.

My initial plan of attack was simple: Find a copy of the game, crack it open in Ghidra, disassemble it to find out how the ski jumping works, and optimize based on the discovered mechanics. As it turned out, each step of this plan was way more involved than anticipated, and created more questions along the way that demanded answers, opening up a rabbit hole of early 90s video game development intricacies. This write-up will take you along on this ride of discovery, learning about how DOS-based programs worked, how video video game developers worked around the hardware limitations, how early copy protection worked, and how GOG sells you a broken version of the game (as of March 2025).

Taking stock - version chaos and copy protection circumvention

The game has had multiple releases, including the original release in 1991, two bundle releases with its successor “Summer Challenge” in 1992 (Europe) and 1996 (US), and a GOG release of the bundle in 2020, based on DOS emulation through DOSBox. While the original floppy disks from my childhood are likely buried somewhere, they are of limited use today for lack of a floppy drive to read them with, so I searched the internet for the game. Acquiring these different versions wasn’t too difficult thanks to the Internet Archive hosting various versions of the original media, and of course purchasing it from GOG.

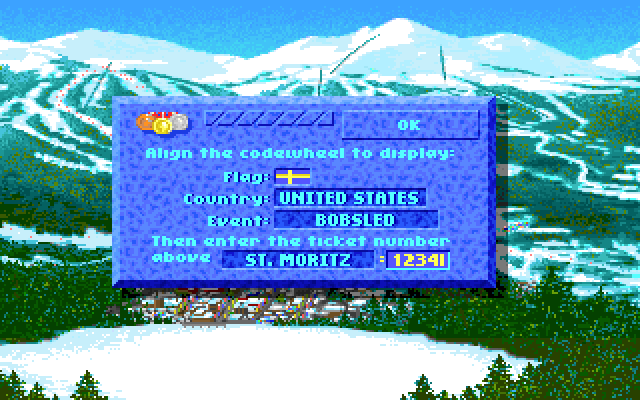

The original game used a code wheel for copy protection. Code wheels were a typical copy protection of the time: They are a physical set of disks sliding against each other, which you got together with the floppy disks containing the game. At startup, the game asks you to turn them in a specific configuration, which reveals a code you need to enter into the game for it to work. For those who are not old like me and have never seen a code wheel before, there is an interactive online version of this game’s code wheel available.

The original 1991 release as expected asks for this code when you try to play any discipline, and boots you out if you answer incorrectly twice.

Side investigation 1: how is the code wheel check implemented?

The GOG version does not ask you for the code and lets you play without it, so presumably they have removed the copy protection from it instead of distributing the code wheel. Where it get very insteresting is that multiple people are complaining in the discussion of this game on GOG that the game is “improperly cracked” and doesn’t work correctly as a result. The descriptions of some of the behaviors, like that you can’t land a ski jump beyond a certain distance, or that you always crash in the last lap of speed skating, actually resonated with my recollection of playing the game as a kid, which means either we had a poorly cracked version back then as well, or that this is not related to copy protection at all and the game is just buggy.

Side investigation 2: Are there hidden copy protection measures which affect gameplay?

The 1996 US release actually comes with a separate crack, presumably officially sanctioned: Next to the main WINTER.EXE, it has a WINTER.COM, only 879 bytes in size, which when executed removes the code wheel check from the game, otherwise the game still asks for it.

But the version confusion doesn’t end there. While searching for different versions, I also found other versions of the game, often in the form of online playable images loaded in DOSBox in the browser. None of these needed a code wheel, and while some were based on the 1996 US release, others used entirely different cracks, created by different release groups of the early 90s.

And to complete the mess, the original game actually offers an option to install the game to disk instead of playing it from floppy, including its very own set of mysteries.

The installation does not work like you might expect, just copying files from floppy to disk; instead, it actually creates a whole new WINTER.EXE executable each time.

During installation, you can choose different options, including which graphics modes to support, and a “fast loading” mode which according to the manual makes the game load faster at the cost of additional hard drive space, and each combination of the options creates a different executable for you.

Side investigation 3: How are these different versions of the executable being created, and how do they differ?

So taking stock and comparing all different acquired versions, there are a lot of distinct binaries:

- The original floppy version of the game

- Six different versions of the game when installed to hard disk, for each combination of “fast loading” and either or both of the EGA and VGA graphics modes

- The GOG version of the game, which is based on the installed VGA+EGA fast-load version with individual bytes modified

- A cracked binary of unknown origin, which is based on the installed VGA fast-load version with individual bytes modified

Furthermore, there are three different stand-alone cracks:

- The official

WINTER.COMcrack (879 bytes) which was provided with the 1996 US release alongside an unmodified floppy version - A

WG.COMcrack (366 bytes) by release group “The Humble Guys” from October 17, 1991, within days after the game’s release - A

WINTER.COMcrack (291 bytes) by release group “Razor1911” from October 17, 1991, the same day(!) as the other crack

Side investigation 4: How do the individual cracks work, and do they use different mechanisms?

Cracking the binary open - obfuscation and memory constraints

So to start somewhere, I loaded up the floppy version in Ghidra, and was immediately underwhelmed. It only managed to analyze a tiny fraction of the initial code, with most of it remaining binary blobs. Opening the same file in IDA revealed much of the same picture, but IDA also provided accompanying warnings: It thinks the binary may be packed, and there are lots of unused bytes beyond the end of the code. I figured that the binary must be packed or obfuscated in some way, and the tiny bit of initial code is the routine to unpack the rest of the binary.

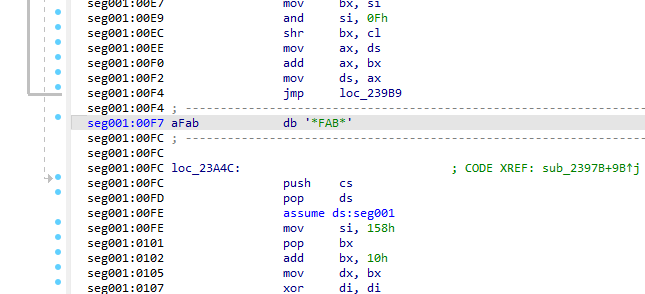

So I began reverse-engineering the unpacking routine, and discovered a suspicious string in the binary, nestled between the assembly: *FAB*.

As it turns out, “FAB” stands for Fabrice Bellard, who next to being the original developer of widely used programs such as FFmpeg and QEMU, is also the creator of an executable compression utility called LZEXE, developed in 1990. Luckily, the inner workings of LZEXE are widely documented and understood. I won’t go into the details of how the compression works here, there are great existing write-ups by Scott Smitelli and Sam Russell if you want to dig deeper. We just want to unpack the binary to get to the good stuff, and there are plenty existing unpacking utilities available, including UNLZEXE by Mitugu Kurizono from the same era. The packing and unpacking is its own arms race microcosm, with protectors to prevent the unpacking, and more sophisticated unpackers to do it anyway, but luckily no additional unpacking protections were employed for this game.

The resulting unpacked binary has two surprises right off the bat: Firstly it is only 168kB in size, much smaller than the original executable despite extraction presumably making it grow in size, and secondly the result of unpacking it is identical across all different versions of the game.

This gives us a hint for how the game is structured: It contains a chunk of business logic, which is what we have unpacked and is the same across versions, and then it contains some resources, like sprites and sounds, which are included into the executable file and loaded out of it at runtime.

This assumption is supported by the fact that the extracted binary actually still works properly as long as it is placed beside the original WINTER.EXE binary to load the assets out of.

But it also is somewhat surprising for the two cracked versions of the binary, I would have expected those to contain modified business logic in order to facilitate skipping the code wheel check.

The answer to that mystery becomes apparent quickly after opening the new extracted binary in a disassembler.

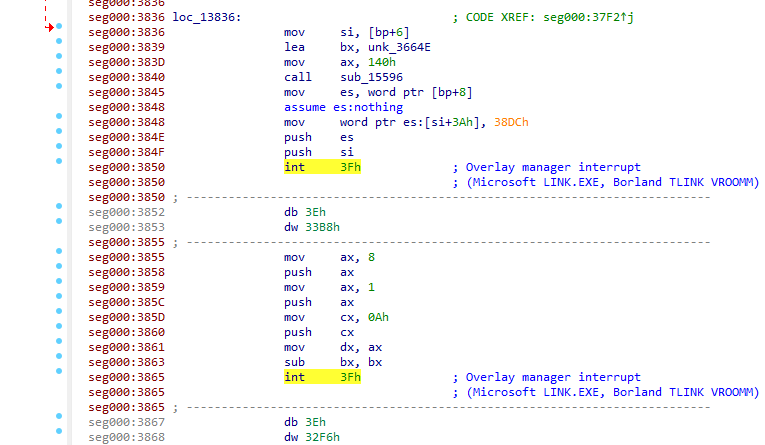

By looking around some, we find suspicious interrupt calls to int 3fh.

Sidebar: Interrupts

Interrupts are the main way DOS programs used to communicate with the operating system, analogous to today’s syscalls. Whenever a program wants to interact with something outside it’s own code, it would call an interrupt and ask DOS to perform that task for it, handing back control to the operating system temporarily, and resuming when it is complete. Anything from printing text to the screen, reading and writing files from disk, to allocating heap memory, is done through the main interrupt DOS provides,

int 21h. Which action is requested and any arguments are determined by the value of the CPU registers when the interrupt is called. Other interrupts exist likeint 33hfor mouse interactions, but notablyint 3fhis not one of the DOS-provided interrupts. Under the hood, the routing of interrupts is handled by an interrupt vector table, which contain for each interrupt the address of the routine that is executed from when the interrupt is called. Programs can modify this table (using an interrupt) to add their own custom interrupts, andint 3fhis likely used-defined this way.

IDA provides a helpful comment to these, that this interrupt is typically used for calling an “Overlay manager”.

Sidebar: Overlays

Overlaying is a technique for loading additional pieces of code at runtime, where multiple such pieces, called overlays, can be swapped out in the same place in memory. This was useful in programs of the time to save on RAM usage: DOS only allowed a maximum of 640kB of memory to be used by a program (aka Conventional memory), and large applications might themselves already be too big to fit all their code into that limit, not even considering any data. Overlays are used to circumvent this limitation: By breaking the program code up into multiple overlays, the program only needs to load whatever overlay is needed for the current operation into memory. Other overlays are loaded from disk as they are needed, replacing the previous overlay, allowing the program to have complex functionality with a small memory footprint. Loading and managing overlays was the responsibility of an overlay manager, a library which kept track of which overlays are needed when and loaded and unloaded them accordingly.

As it turns out, the game was written in C and compiled with the Microsoft C compiler version 6, as hinted by an embedded string MS Run-Time Library - Copyright (c) 1990, Microsoft Corp in the binary.

Perusing the compiler’s manual, the linker of that compiler did natively support overlays and would install its own overlay manager as int 3fh by default, so this was my first suspicion for how this structure was created.

Overall, this was not good news. It means that the unpacked binary is in fact not all the business logic that exists, and there are more pieces of code, presumably in the resources packaged with the executable. Disassemblers don’t understand these overlays, can’t detect them or automatically disassemble them, so the work to understand the business logic will be more manual than planned. In order to progress further, we need to find and extract all these overlays, to get a complete picture of the game’s code.

By finding where the interrupt 3fh is installed at the start of the program, we can identify the overlay manager routine which is called each time an overlay is needed.

Based on documentation for how Microsoft’s overlay manager worked, each interrupt call is followed by 3 bytes, one byte for the index number of the overlay that is needed, and two for the 16-bit address within that overlay. Calling the interrupt then works like a function call: The overlay is loaded, the function at the given address is invoked, and afterwards the control flow returns directly after the interrupt call. In fact the interrupts are literal replacements for function calls: a the 5 bytes typically needed for a far call instruction (1 byte opcode, 2 bytes address offset, 2 bytes address segment) are replaced by the Linker with the 5 bytes for the interrupt (2 bytes opcode, 1 byte overlay index, 2 bytes address offset) where needed.

This is where the good news ended though. According to the documentation, each overlay should be appended to the main program, including its own MZ header, but this is not what we find in our binary. Worse still, when using DOSBox’ debugger to step through an invocation of the interrupt, the code that was loaded is nowhere to be found in the binary file. Also, unlike typical overlays, they are not actually occupying the same space in memory, instead new memory is dynamically allocated for each overlay, and deallocated after use. That is useful because it allows multiple overlays to be loaded at the same time, but also means this game is not actually using the overlay mechanism from Microsoft C, instead it uses what appears to be a bespoke overlay management implementation.

Extracting the resources

Statically reverse-engineering the overlay manager routine turned out to be a very time-consuming endeavor, but luckily there were still some hints that can help us take some shortcuts.

The DOS emulator DOSBox-X is a fork of DOSBox, and has additional useful debugging features, including logging of all file IO, and all int 21h interrupts.

Watching those while the game starts up reveals that the game is seeking through the binary to specific locations, which happen to be directly after the bytes of the main program, and then reading many chunks of 22 bytes each.

...

4201235 DEBUG FILES:Seeking to 82944 bytes from position type (0) in WINTER.EXE

4201290 DEBUG FILES:Reading 2 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4201353 DEBUG FILES:Seeking to 82495 bytes from position type (0) in WINTER.EXE

4201408 DEBUG FILES:Reading 2 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4201475 DEBUG FILES:Seeking to 82497 bytes from position type (0) in WINTER.EXE

4201530 DEBUG FILES:Reading 2 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4204681 DEBUG FILES:Seeking to 82499 bytes from position type (0) in WINTER.EXE

4204735 DEBUG FILES:Reading 22 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4204855 DEBUG FILES:Reading 22 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4204975 DEBUG FILES:Reading 22 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4205095 DEBUG FILES:Reading 22 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4205215 DEBUG FILES:Reading 22 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4205335 DEBUG FILES:Reading 22 bytes from WINTER.EXE

4205455 DEBUG FILES:Reading 22 bytes from WINTER.EXE

...

These are likely the start of the resources, and when checking the binary at that location we find that the section begins with two bytes spelling out MB, similar to how the executables themselves start with an MZ magic number.

Looking for this magic number in the disassembly brings us directly to the routine which parses out the structure of the embedded resources.

seg000:6D83 sub ax, ax ; sets ax to 0

seg000:6D85 push ax ; push argument 3 for fseek: 0 = seek relative to start of file

seg000:6D86 push winter_exe_overlay_start_index_hi ; push argument 2 for fseek: the offset to seek to

seg000:6D8A push winter_exe_overlay_start_index_lo ; it's a 4 byte value and pushed in two halves

seg000:6D8E push winter_exe_file_handle ; push argument 1 for fseek: the file handle of WINTER.EXE which was opened earlier

seg000:6D92 call fseek ; seek to the start of the resource section in the WINTER.EXE file

seg000:6D97 add sp, 8 ; clear the arguments for fseek from the stack again

seg000:6D9A push cs ; the function read_2_bytes_from_winter_exe is a far function, but we're making in near call, so we need to push the segment onto the stack manually

seg000:6D9B call near ptr read_2_bytes_from_winter_exe ; read the next two bytes from the file

seg000:6D9E cmp ax, 424Dh ; check if if contains the "MB" magic number

seg000:6DA1 jz short mb_marker_found ; jump if found

seg000:6DA3 push winter_exe_file_handle ; if not found, close file and return

seg000:6DA7 call fclose

seg000:6DAC add sp, 2

seg000:6DAF mov winter_exe_file_handle, 0

seg000:6DB5 jmp short done

seg000:6DB5 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:6DB8 mb_marker_found:

seg000:6DB8 sub ax, ax ; sets ax to 0

seg000:6DBA push ax ; push argument 3 for fseek: 0 = seek relative to start of file

seg000:6DBB mov ax, winter_exe_overlay_start_index_lo ; load overlay start index and add 2 to it

seg000:6DBE mov dx, winter_exe_overlay_start_index_hi

seg000:6DC2 add ax, 2

seg000:6DC5 adc dx, 0

seg000:6DC8 push dx ; push argument 2 for fseek: the offset to seek to

seg000:6DC9 push ax

seg000:6DCA push winter_exe_file_handle ; push argument 1 for fseek: the file handle of WINTER.EXE which was opened earlier

seg000:6DCE call fseek ; seek to the next two bytes after the MB marker

seg000:6DD3 add sp, 8 ; clear the arguments for fseek from the stack again

seg000:6DD6 push cs

seg000:6DD7 call near ptr read_2_bytes_from_winter_exe ; read the next two bytes from the file

seg000:6DDA mov resource_chunk_count, ax ; next two bytes indicate the number of resources

seg000:6DDD done:

....

Sidebar: 16-bit architecture and segments

This program, and all DOS programs at the time, were built for a 16-bit architecture, compared to the 64-bit architecture today’s computers are using. What that means is that all registers in the CPU can hold only 16-bit values, including any pointers. Since 16-bit registers can only have 2^16 = 65536 different values, it can only address 64kB of memory. This was too little, even back then, so in order to be able to address more memory, pointers typically consisted of 2 parts, a segment and an offset.

Segments are chunks of memory, at most 64kB in size, which were typically assigned different roles: there are typically one or multiple code segments holding the program code, a data segment holding the work memory for any data the program stores, and a stack segment to hold the values which are put on the stack. Those segments can be considered independent parts of the memory, and to interact with something from another segment, you would need a far pointer, consisting of both a segment and offset within that segment, whereas for referencing something within a segment a near pointer using only the offset is sufficient.

Under the hood, the memory is still one linear chunk, and the resulting memory address of a far pointer is simply

segment * 16 + offset. That means segments can technically overlap with different segment-offset pairs pointing to the same physical address, but conventionally they were chosen to be distinct blocks.

The resources are all tabulated in a simple header structure, in entries of 22 bytes each.

Each entry contains two 4-byte numbers, indicating the length of the data and the offset in the file where they are located.

The remaining bytes contains a 0-terminated string spelling out the name of the resource (any byte after the 0 terminator is garbage).

However, this name is obfuscated by adding 0x60 to all bytes, so they don’t show up in any strings analysis of the binary.

By de-obfuscating the names, we can learn that these additional binary blobs contain both the assets like images, meshes, music and SFX files, and the code overlays in the form of pairs of files with extensions COD and REL.

4D 42 ; "MB" = magic number

F2 00 ; 242 = number of resources

4A 5C 00 00 10 57 01 00 B4 A9 B4 AC A5 8E AD B3 A8 00 (81 9F A2 01) ; Resource TITLE.MSH start 15710 end 1b35a length 5c4a

26 24 00 00 5A B3 01 00 B4 A9 B4 AC A5 8E AD A7 B3 00 (81 9F A2 01) ; Resource TITLE.MGS start 1b35a end 1d780 length 2426

9E D4 00 00 80 D7 01 00 B4 A9 B4 AC A5 8E AD B0 A9 00 (81 9F A2 01) ; Resource TITLE.MPI start 1d780 end 2ac1e length d49e

00 03 00 00 1E AC 02 00 B4 A9 B4 AC A5 B0 A1 AC 8E A2 A9 AE 00 (01) ; Resource TITLEPAL.BIN start 2ac1e end 2af1e length 300

2E 4A 00 00 1E AF 02 00 B4 A9 B4 AC A5 92 8E AD B3 A8 00 (AE 00 01) ; Resource TITLE2.MSH start 2af1e end 2f94c length 4a2e

56 1B 00 00 4C F9 02 00 B4 A9 B4 AC A5 92 8E AD A7 B3 00 (AE 00 01) ; Resource TITLE2.MGS start 2f94c end 314a2 length 1b56

44 CC 00 00 A2 14 03 00 A2 A1 A3 AB A4 B2 AF B0 8E AD B0 A9 00 (01) ; Resource BACKDROP.MPI start 314a2 end 3e0e6 length cc44

92 65 00 00 E6 E0 03 00 A9 B3 8E AD B3 A8 00 (B0 8E AD B0 A9 00 01) ; Resource IS.MSH start 3e0e6 end 44678 length 6592

CC 18 00 00 78 46 04 00 A9 B3 8E AD A7 B3 00 (B0 8E AD B0 A9 00 01) ; Resource IS.MGS start 44678 end 45f44 length 18cc

D8 88 00 00 44 5F 04 00 B4 A1 BF AF B0 A5 AE 8E AD A7 B3 00 (00 01) ; Resource TA_OPEN.MGS start 45f44 end 4e81c length 88d8

D8 73 00 00 1C E8 04 00 B4 A1 BF AF B0 A5 AE 8E AD B3 A8 00 (00 01) ; Resource TA_OPEN.MSH start 4e81c end 55bf4 length 73d8

00 07 00 00 F4 5B 05 00 A5 B6 B4 A1 B7 A1 B2 A4 8E AD A7 B3 00 (01) ; Resource EVTAWARD.MGS start 55bf4 end 562f4 length 700

22 24 00 00 F4 62 05 00 A5 B6 B4 A1 B7 A1 B2 A4 8E AD B3 A8 00 (01) ; Resource EVTAWARD.MSH start 562f4 end 58716 length 2422

CC 56 00 00 16 87 05 00 A9 B3 A1 B5 B8 8E AD B3 A8 00 (B3 A8 00 01) ; Resource ISAUX.MSH start 58716 end 5dde2 length 56cc

32 25 00 00 E2 DD 05 00 A9 B3 A1 B5 B8 8E AD A7 B3 00 (B3 A8 00 01) ; Resource ISAUX.MGS start 5dde2 end 60314 length 2532

...

64 27 00 00 96 AF 12 00 AF B6 AC 91 8E A3 AF A4 00 (B3 00 AE 00 01) ; Resource OVL1.COD start 12af96 end 12d6fa length 2764

6E 03 00 00 FA D6 12 00 AF B6 AC 91 8E B2 A5 AC 00 (B3 00 AE 00 01) ; Resource OVL1.REL start 12d6fa end 12da68 length 36e

35 02 00 00 68 DA 12 00 AF B6 AC 91 95 8E B0 A3 AF 00 (00 AE 00 01) ; Resource OVL15.PCO start 12da68 end 12dc9d length 235

11 00 00 00 9E DC 12 00 AF B6 AC 91 95 8E B0 B2 A5 00 (00 AE 00 01) ; Resource OVL15.PRE start 12dc9e end 12dcaf length 11

...

One fun pattern to observe is that the garbage data after the file names are leftovers from the previous name, suggesting that when the entries were written, it used the same buffer for all names in order.

Just from the names, we can assume that the COD files contain the actual machine code, and the REL files contain some relocation data.

Sidebar: Relocations

Relocation is a concept that allows code to become location-independent: When a program is loaded into memory, it may not be loaded at the same address every time. However, parts of the program refer to other parts by address (e.g. a function call), and in order for those to continue to work regardless of the actual location in memory, they need to be modified. To achieve this, all addresses are written into the binary as if the program is located at memory address 0, and all the places which correspond to segment values are put in a long list called the relocation table. For the main program, this is handled by DOS: the MZ header of the executable contains a relocation table with addresses in the code that need to be updated. After copying the program into memory at some offset, DOS goes through this list and adds the chosen offset to each of the addresses it contains, making all far pointers point to the correct locations again.

When loading these code overlays, the same problem of relocation will exist, and the

RELfiles likely contain the needed information to facilitate their proper relocation.

When looking at the different versions of the installed game, we can see that the resources they are bundled with are indeed different. This finally resolves the first of our side mysteries:

Side investigation 3 complete! Depending on the chosen graphics mode, more or fewer assets are included, and each asset can come in two variants, the uncompressed version (e.g.

TITLE.MGS), and a compressed version (e.g.TITLE.PMG), indicated by prepending aPto its extension. The “fast loading” versions of the installation bundle the uncompressed resources, while the floppy version contains the packed versions, providing a trade-off between speed of loading the assets at runtime and the size they take up on disk.

It’s difficult to imagine nowadays, but hard drive space was a serious concern back then, and the additional kilobytes the unpacked assets take up could matter a lot.

However, it seems that even in the fast-loading versions, not all assets are actually uncompressed. Specifically some of the code overlays stay packed even there, presumably as a means to keep them obfuscated even when fast loading is selected during installation. However, through disassembly we already know where the resources are loaded now, so using a debugger with appropriate breakpoints, we can easily dump the uncompressed versions for these as well out of the program memory, without needing to understand how the compression of the resources actually works. (If you are still curious how the compression works, I did end up disassembling it to find that it’s a surprisingly sophisticated custom variant of DEFLATE compression. You can find a JS re-implementation of it here.)

Conveniently, the game also provides us with a fairly easy way to check whether we extracted all the resources correctly. It turns out the game is more flexible with where it tries to load the resources from, and not only checks the embedded resources in the binary, but also checks for individual files of the same name, in the root folder or a subfolder called “ART”. As long as the resource can be found in any of these places, it will use it. So by writing a program to extract all these resources into their own files and placing them in the ART subfolder, and then manually modifying the binary to delete all embedded resources, we can make the game use our extracted assets instead. Doing this and running the game, it is indeed still working, confirming that our extracted resources are accurate and we’re not missing anything else coming from the binary file.

Combining all overlays

So now we finally have all the code comprising the business logic of the game, but they are spread out over 17 files, the main executable and 16 overlays, making them very annoying to work with.

What we would like is one single binary with all the code in it, making it much easier to analyze.

To achieve this, we can try to embed the overlays into the binary, essentially undoing the overlaying and having all of them loaded at once side-by-side.

Even more, doing this allows us to undo the replacement of the function calls with overlay interrupts, eliminating int 3fh altogether and making the automatic analysis by common disassemblers much more accurate.

Available RAM is obviously not a concern anymore today, but we will still need to stay within the 640kB limit DOS imposes.

Luckily, all overlays combined are only around 100kB in size, so together with the main binary of 168kB it should still leave enough room to load the assets as needed, especially since it won’t need to reserve heap space anymore loading the overlays.

Actually fusing the binaries together is not that easy unfortunately. My first idea of just concatenating all overlays onto the main binary in memory and baking in the relocations to make them all connect sadly wouldn’t work, because of the stack and how dynamic memory allocations work. The main binary is set up in a way where all code segments come first, then the data segment holding all the work memory the program uses, and lastly the stack segment. Trying to append the overlays to this will always create some issues: Adding them before the data segment would mean we need to re-write all references to it throughout the code, which are hard to identify because the line between the data and stack areas are fuzzy and the code might do some pointer arithmetic that relies on the relative positions of the segments. Adding the overlays after data segment by moving the stack back is also impossible, because the game does some weird shenanigans where it sets the stack segment to equal the data segment, adjusting the stack pointer accordingly to compensate. This is probably useful as an invariant for optimization, but also means that the data and stack segments need to be close together in memory to allow that. And finally, placing it after the stack, where they are typically loaded using the overlay manager, has problems as well because it would conflict with heap allocations.

Sidebar: Heap allocations

Memory management worked completely differently back in the DOS days compared to now. While modern operating systems all work with virtual memory where each program has its own address space completely to itself, and the operating system translates them to the physical RAM addresses, DOS programs ran in what is called 16-bit Real Mode, which uses the actual physical addresses directly. That means programs had direct control over the entire RAM of the system, and could just read and write to it as they pleased. This worked, mostly because you could only run one DOS program at a time anyway, so they didn’t need to share memory with others.

So allocating memory really didn’t mean much since it was all yours anyway, and programs typically started out with “owning” the entire memory space. DOS still provided an allocator, but in order to use it your program first needed to deallocate some of the memory space and give it back to DOS, so that new blocks can be allocated in this space. This game does this, and in order to determine how much it can free up, it performs some calculations based on the addresses it happens to be loaded into.

So by just appending the overlays, we would interfere with the allocated memory, and while we could try to patch the program to avoid this, it may cause other unexpected side effects.

The solution to this conundrum, as always obvious only in hindsight, is to not add the overlays after the main program, but before it. Since programs are created to be location-independent and can work anywhere in memory, moving it back in order to make space for the overlays can be done completely safely. And since the overlays are normally heap allocated and can be anywhere in relation to the main program, there is no reason why that anywhere couldn’t be also before the main program.

To test this concept, I first created a new binary which only padded out the beginning of the binary by the needed amount without actually placing the overlays into it. This can be done without needing to disassemble its contents at all, just using the relocation information in the MZ header to identify all the places where addresses need to be adjusted, and updating the header information to push the segments backwards. The resulting binary still works perfectly, proving not only that the concept works, but also that the remaining memory is sufficient for everything else the game still needs to load.

In a second step, we can now place all the overlay code in the newly available space, and wire it up.

For each call of the int 3fh interrupt, we can extract which overlay and which location in the overlay it would normally go to, and replace it with a direct far call to that address in the now-embedded overlays.

The overlays themselves also need to be adjusted using their relocation information, with a small additional caveat: within the overlays there are two types of relocations, the addresses that point back into the main program, and the addresses which point to other areas within the same overlay. The game contains special logic to handle both cases when it loads the overlays, which we need to replicate here, by checking which area of memory an address points to before applying the relocations.

We also need to append all the relocation information for the overlays to the relocation table of the main program, because the new combined binary can of course still be loaded into memory at any location, so the addresses need to be adjusted accordingly.

What we end up with is a completely self-contained binary, which does not need to load any more overlays to work, and which doesn’t contain any overlay interrupts anymore. Together with the extracted art assets in separate files, we now have an unpacked and unobfuscated, still perfectly playable, version of the game.

It’s worth noting that this was not guaranteed to actually work. Replacing the overlay interrupts with function calls has the same behavior, but the overlay manager itself which is now sidestepped has additional side effects which could be critical for the game to work. One notable instance of this in the game is the logic it uses to unload overlays: To detect which memory addresses to deallocate, it inspects the actual code of the program, parses the interrupt call opcodes, and extracts the information out of it in order to determine which overlay is affected.

seg000:D91F maybe_unload_overlay_for_call:

seg000:D91F push bp ; save base pointer register on the stack, to restore it later

seg000:D920 mov bp, sp ; set base pointer to current stack pointer. This means all arguments are some fixed offset from bp

seg000:D922 les bx, [bp+6] ; Read the far pointer that was provided as an argument, and store it in es:bx

seg000:D925 cmp byte ptr es:[bx], 0CDh ; Check if at the given address is a CD byte, which is an int instruction

seg000:D929 jz short unload ; if it is any int instruction, proceed (doesn't check what interrupt it actually is)

seg000:D92B jmp short skip_unloading

seg000:D92D ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:D92D unload:

seg000:D92D mov bl, es:[bx+2] ; Read the overlay index following the int instruction to know which overlay to unload

seg000:D931 call unload_overlay ; unload the overlay

seg000:D934

seg000:D934 skip_unloading:

seg000:D934 pop bp ; restore the base pointer stored at the start of the function

seg000:D935 retf

Luckily, the game has built-in fallbacks to skip this step if the code locations don’t actually contain an interrupt but instead a far call. Presumably, because it was not known ahead of time which pieces of code would end up in which overlay, they couldn’t know for sure which calls would end up being interrupts instead so they needed to handle both cases. For us this is lucky because it means that even after replacing all interrupts with function calls, the overlay management code can handle it correctly and doesn’t try to unload our baked-in overlays.

The anti-debugger check - Part 1: obfuscation and assembly trickery

With all the prep work done, we can now take a look at the inner workings of the game in earnest, starting with looking at the copy protection and the claims of improperly cracked versions causing gameplay issues. Besides the main code wheel protection, the game actually has another defense mechanism, an anti-debugger check. That anti-debugger check consists of two parts.

The first and simplest one is that the game checks for the existence of known debuggers in its path.

It tries to open three files with the file names NU-MEGA, SOFTICE1 and TDHDEBUG, and if any of these exist, the game will not let you get past the main menu.

As you might guess, these names correspond to popular DOS-based debuggers, so if it detects you are using any of these, it will refuse operation.

The names of these files is obfuscated in the code using the xor operation, similar to the resource file names, and the check is buried in between other code initializing the intro sequence, but by logging the file IO the program performs they are easy to spot.

seg001:039C check_for_known_debuggers:

seg001:039C push bp ; save base pointer register on the stack, to restore it later

seg001:039D mov bp, sp ; set base pointer to current stack pointer. This means all arguments are some fixed offset from bp

seg001:039F sub sp, 40h ; reserve additional space on the stack

seg001:03A2 push di ; save di and si registers on the stack, to restore them after the function is done

seg001:03A3 push si

seg001:03A4 sub si, si ; set si to 0

seg001:03A6 cmp obfuscatedNuMegaFileName, 0 ; check if file name exists in memory

seg001:03AB jz short file_name_empty_skip ; skip decoding if its empty

seg001:03AD decode_file_name_loop:

seg001:03AD mov al, obfuscatedNuMegaFileName[si] ; read next byte of file name

seg001:03B1 xor al, 0A5h ; de-obfuscate byte

seg001:03B3 mov [bp+si+40h], al ; store in the space created on the stack

seg001:03B6 inc si ; move to next byte

seg001:03B7 cmp nuMegaFileName[si], 0 ; reached end of file name yet?

seg001:03BC jnz short decode_file_name_loop ; loop if more characters available

seg001:03BE file_name_empty_skip:

seg001:03BE mov [bp+si+40h], 0 ; terminate decoded file name with 0

seg001:03C2 mov ax, 8000h

seg001:03C5 push ax ; argument 2 for file read function, not important here

seg001:03C6 lea ax, [bp+40h]

seg001:03C9 push ax ; argument 1 for file read function, pointer to decoded file name

seg001:03CA call open_file_for_read ; try to open file

seg001:03CF add sp, 4 ; remove arguments from stack again

seg001:03D2 mov di, ax

seg001:03D4 cmp di, 0FFFFh ; check if opening the file succeeded

seg001:03D7 jz short next ; opening failed, move on to next file name to check

seg001:03D9 mov detected_debugger_binary, 1 ; debugger detected, set flag

seg001:03DF push di ; argument 1 for close file, the file handle

seg001:03E0 call close_file_handle ; close the opened file again

seg001:03E5 add sp, 2 ; remove arguments from stack again

seg001:03E8 next:

...

When we’re trying to follow where this debugger check flag is used, we see it is moved around from one memory address to the next a couple of times. Here, the game also starts throwing misdirections at us to make deciphering it harder:

seg010:0000 propagate_debugger_check_1:

seg010:0000 push bp ; save bp to stack, standard preamble for a function call

seg010:0001 mov bp, sp ; set base pointer to current stack pointer. This means all arguments are some fixed offset from bp

seg010:0003 sub sp, 8 ; make space on stack for local variables

seg010:0006 mov ah, 2Ch

seg010:0008 int 21h ; int 21h ah=2c returns the current system time

seg010:000A push dx ; argument 1: seconds and hundreds of the system time

seg010:000B call process_current_time_result

seg010:000E add sp, 2

seg010:0011 mov cx, 4A52h

seg010:0014 mov bx, data_segment

seg010:0017 mov es, bx

seg010:0019 mov es:debugger_check_result_4E62A, cl

...

seg010:0029 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg010:0029 process_current_time_result:

seg010:0029 push bp ; save bp to stack, standard preamble for a function call

seg010:002A mov bp, sp ; set base pointer to current stack pointer. This means all arguments are some fixed offset from bp

seg010:002C mov bx, 0Fh ; bx = 15 (?)

seg010:002F mov cx, detected_debugger_binary

seg010:0033 mov ax, cx

seg010:0035 imul bx ; multiplies detected_debugger_binary by 15 (?)

seg010:0037 mov ax, [bp+4] ; reads seconds and hundreds into ax (?)

seg010:003A xchg al, ah ; swaps seconds and hundreds part (?)

seg010:003C sub bl, 3 ; bx = 12 (?)

seg010:003F sub bp, 2 ; modifies the base pointer. This is very sneaky, as it fundamentally changes what the operation seg010:0054 below does.

seg010:0042 add al, ah ; add seconds and hundreds part together (?)

seg010:0044 sub ah, ah

seg010:0046 idiv bx ; divide by 12 (?)

seg010:0048 mov ax, segment_42

seg010:004B mov es, ax

seg010:004D mov es:code_wheel_flag_index_input_4A090, dx ; this is later used as "random" input for the code wheel check

seg010:0052 shr bx, 1 ; bx = 6 (?)

seg010:0054 add [bp+4], 6 ; The magic happens here: Because of the modified bp, this doesn't modify the argument, but the return address of the function

seg010:0058 pop bp

seg010:0059 retn ; because of the changed return address, it will skip the instructions at seg010:000E and seg010:0011 after returning!

This is a very misleading piece of code that would make any malware developer jealous.

At first glance, it appears to read the current time and process it, and then write a constant 4A52h to register cx and later into debugger_check_result_4E62A.

However, the process_current_time_result does some weird things instead.

For one, most of the operations (I marked them with question marks) don’t actually contribute anything, they are purely there to confuse you.

The operation that actually matters and is trying to hide is the modification of the base pointer at seg010:003F.

This, in combination with the instruction at seg010:0054, modify the return address of the function, increasing it by 6.

This means instead of returning at seg010:000E like it should, it will instead return at seg010:0014, skipping setting cx to the constant value.

So the value that is actually propagated into debugger_check_result_4E62A is the detected_debugger_binary which was loaded into cx, all the other operations are just misdirection.

This kind of misdirection is clearly intended to make disassembly deliberately harder and stop people from reverse engineering the copy protections. We will see more of it as we move on.

The anti-debugger check - Part 2: Modern computers are too fast

The debugger check result flag is moved around two more times:

...

seg011:003C mov al, es:debugger_check_result_4E62A

seg011:0040 mov bx, seg segment_39

seg011:0043 mov es, bx

seg011:0045 mov es:debugger_check_result_47A70, al

...

and finally

...

seg000:0355 mov al, es:debugger_check_result_47A70

seg000:0359 sub ah, ah

seg000:035B mov debugger_check_result, ax

...

These two moves are the second debugger check the game does, which is more technical and based on the Intel 8253 timer chip.

The first move is performed inside a timer interrupt handler which the game installs, and which is triggered by the aforementioned timer chip. Later during the initialization, the game then runs the second move of the flag to its final location, which is ultimately the one that is checked to decide whether you passed or failed. That means that this timer interrupt is expected to be triggered at the right moment, after the initial known debugger check has been performed, but before the value is looked up later during initialization. If the timer is triggered too early or too late with respect to the initialization, the the check won’t pass. This check would prevent you from stepping through the initialization code, because the timer interrupt will fire too early, or emulate it in some way that doesn’t consider hardware interrupts.

For modern DOS emulators like DOSBox, this is not a problem and they are accurate enough to be able to pass the check easily. The main issue arises from modern computers being too fast: if your emulation speed is too high, especially if you use the fast-loading version of the game, it breezes through the initialization so fast that it is done before the timer interrupt could trigger, making you fail the check. The simple solution to this problem therefore is to slow down the emulator before starting the game. After it is in the main menu, you can speed it up again without adverse effects. Especially our home-cooked fully unpacked version loads so blazingly fast, that I need to slow down the emulator to a crawl in order to still pass the check. This is because unpacking the resources from the executable is itself much slower than loading individual files, even if they are not compressed, because it needs to linearly scan through the whole resource list for every resource, whereas the (emulated) file IO takes no time at all.

seg000:0D42 perform_debugger_check:

seg000:0D42 push bp

seg000:0D43 mov bp, sp

seg000:0D45 or ax, ax ; ax contains debugger_check_result, check if it succeeded

seg000:0D47 jz short check_passed ; if equals 0, it succeeded

seg000:0D49 call sub_12846 ; changes back to text mode

seg000:0D4E mov ax, offset aPleaseRemove ; "Please remove your debugger before running The Games: Winter Challenge"

seg000:0D51 push ax

seg000:0D52 call println ; prints error message to screen

seg000:0D57 mov sp, bp

seg000:0D59 sub ax, ax

seg000:0D5B push ax

seg000:0D5C call sub_2F8CE ; exits game

seg000:0D61

seg000:0D61 check_passed:

seg000:0D61 mov sp, bp

seg000:0D63 pop bp

seg000:0D64 retn

Slowing down the emulator each time to pass the check gets annoying quickly though.

Luckily, the debugger check is done in a single place, and is easily removed without any adverse effects, by modifying the conditional jump at seg000:0D47 to be an unconditional jump instead.

We have now partially cracked the game, hurray!

That was the appetizer though, the main course is still to come and it’s a doozy.

The code wheel check - A honey pot for crackers

The code wheel protection is in principle less technical and more straight-forward: The game reads the number you enter, it then looks up what the answer should have been, and checks whether they match. Thanks to our fully unpacked executable, finding where this check is made is as simple as finding the error message (“That ticket number is incorrect. Try again.”) in the binary, and looking for references to it, places in the code where it is used. Placing debugger breakpoints on this function and stepping through it lets us identify which sections are roughly responsible for which parts of the process.

Through this process, we can identify the heart of the protection: a function which takes the randomly generated code wheel configuration and the entered ticket number as an input, and decides whether it was entered correctly or not. It doesn’t do any assembly trickery, but it contains some unnecessary operations as misdirection. We can translate it to some more compact pseudo code:

code_wheel_check_answer(city_index, flag_index, country_index, discipline_index, ticket_number): # at seg007:0260

# determine how high the slot cutout for the chosen city is on the inner wheel, values 0(innermost) - 5(outermost)

slot_height = slot_height_table[city_index]

code_wheel_ticket_number_4A890 = ticket_number

# determine slot position relative to chosen discipline, values 0-11 clockwise

slot_position = (city - ((city + 1) >> 2)) - discipline_index

code_wheel_ticket_number_4A892 = ticket_number

if slot_position < 0:

slot_position += 12

# determine which sector of the outer wheel is under the slot

flag_wheel_sector = (flag_index + slot_position) % 12

code_wheel_ticket_number_4A894 = ticket_number

# do unnecessary operations as misdirection

rand = random_number()

alloc = allocate_memory(rand % 1000)

deallocate_memory(alloc)

# determine which sector of the middle wheel is under the slot

country_wheel_sector = (country_index + slot_position) % 12

# read expected answer from obfuscated table

obfuscated_ticket = country_wheel_data[country_wheel_sector * 6 + slot_height]

code_wheel_ticket_number_4A898 = ticket_number

if obfuscated_ticket == 0xa283: # hole in the middle wheel, use outer wheel data instead

obfuscated_ticket = flag_wheel_data[flag_wheel_sector * 6 + slot_height]

code_wheel_ticket_number_4A89C = ticket_number

return ticket_number ^ 0xa283 == obfuscated_ticket

Apart from the random memory allocation and deallocation providing some red herrings, the actual checking logic is fairly straight-forward and directly simulates how the physical code wheel functions. It considers how the discs are rotated, and then checks which number will be visible on the wheel based on a table of all the possible answers.

Side investigation 1 complete!

But besides the immediate check, it also places the ticket number into 5 different places in memory. Those 5 memory locations are where it gets interesting, because looking at where they are used, they all re-appear in the same location:

seg015:0000 code_wheel_calculate_derived_ticket_numbers:

seg015:0000 push si

seg015:0001 mov es, segment_47

seg015:0005 mov ax, es:code_wheel_ticket_number_4A890

seg015:0009 xor ax, 0C514h

seg015:000C mov cx, ax

seg015:000E shl ax, 1

seg015:0010 add ax, cx

seg015:0012 mov es, segment_47

seg015:0016 mov es:ticket_xor_c514_mul_3, ax

seg015:001A mov es, segment_47

seg015:001E mov ax, es:code_wheel_ticket_number_4A892

seg015:0022 xor ax, 0C514h

seg015:0025 add ax, 38D9h

seg015:0028 mov es, segment_47

seg015:002C mov es:ticket_xor_c514_plus_38d9, ax

seg015:0030 mov es, segment_47

seg015:0034 mov cx, es:code_wheel_ticket_number_4A89C

seg015:0039 xor cx, 0C514h

seg015:003D sub cx, 37Ch

seg015:0041 mov es, segment_47

seg015:0045 mov es:ticket_xor_c514_sub_37c, cx

seg015:004A mov es, segment_47

seg015:004E mov cx, es:code_wheel_ticket_number_4A898

seg015:0053 xor cx, 8E47h

seg015:0057 mov es, segment_47

seg015:005B mov es:ticket_xor_8e47, cx

seg015:0060 mov bx, 7

seg015:0063 mov es, segment_47

seg015:0067 mov dx, ax

seg015:0069 mov ax, es:code_wheel_ticket_number_4A894

seg015:006D xor ax, 0C514h

seg015:0070 mov si, dx

seg015:0072 sub dx, dx

seg015:0074 loc_29284:

seg015:0074 div bx

seg015:0076 mov es, segment_47

seg015:007A mov es:ticket_xor_c514_div_7, ax

seg015:007E add cx, si

seg015:0080 mov es, segment_47

seg015:0084 mov es:ticket_xor_c514_plus_38d9_allplus_ticket_xor_8e47, cx

seg015:0089 pop si

seg015:008A retf

In this code snippet, the 5 copies of the ticket number are modified in various ways to create 6 new values derived from it, with some arbitrary operations to make them all different.

Each of these six values is used some specific place elsewhere in the code, where it is compared against some reference value.

If we try to find out where those reference values come from, what we find it a second copy of the code wheel answer checking routine from above, complete with a second instance of the table containing all correct answers!

The only difference between the two is that is uses a different value to xor the ticket numbers with, using 0xc514 instead of 0xa283.

Afterwards, the same arbitrary operations are applied to them to create the 6 reference values.

Side investigation 2 complete!

The hidden copy protection checks are real! The game performs more hidden code wheel checks throughout the game, in each of these 6 locations. If the main code wheel check is merely skipped, these hidden checks will fail and the game knows you tried to circumvent the copy protection. When that happens, it will mess with the game in more subtle ways, to sabotage your illegitimate play session. This is a sneaky additional layer of copy protection, where if you try to crack the game and remove the obvious checks, you might not even realize these additional checks exist, unless you pick up on the gameplay alterations.

What do the hidden copy protection checks do?

To find out what gameplay alterations the game performs when the checks fail, the easiest way is to set breakpoints at each of these locations, and then play the various disciplines waiting for them to trigger. This lets us easily discover what each of the hidden checks do.

Even better, thanks to the replay feature, we can record a replay with a proper version, and then play it back in a version where the hidden checks activate, in order to see what difference they make on the same set of inputs.

Ski Jump

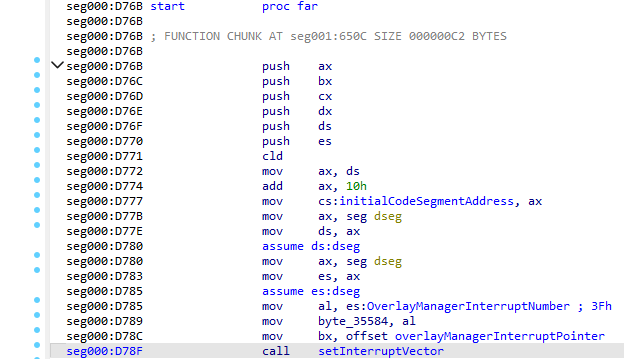

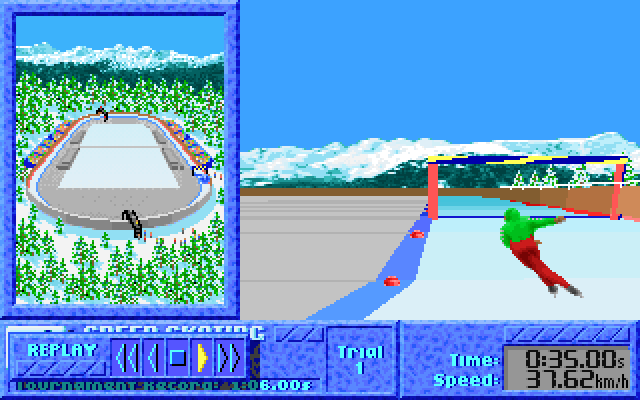

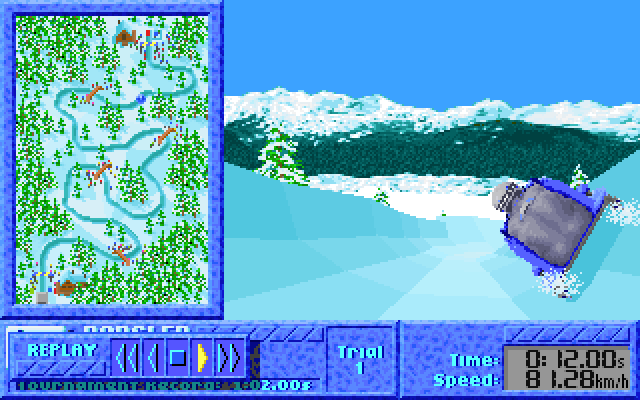

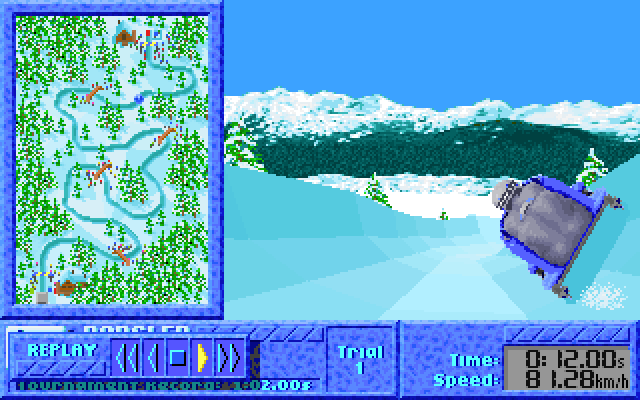

One of the most obvious changes we find in the skip jump event: When the copy protection check fails, any attempt land a ski jump beyond a certain distance fails. More specifically, beyond a distance of 86.7m, the game won’t recognize you pressing Enter to land your jump anymore:

(if the two animations are not in sync, try reloading this page in a new tab or click here)

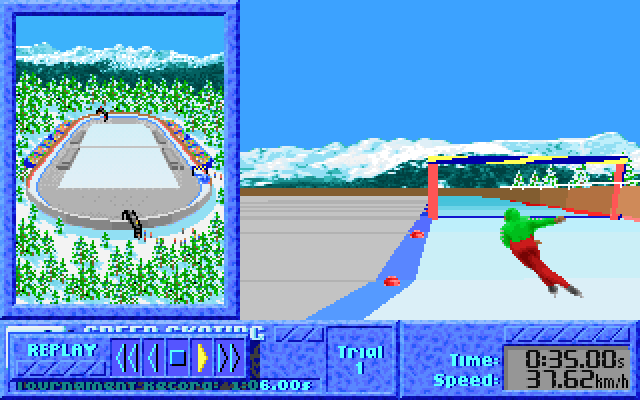

Speed Skating

This is the second very obvious change: In the third lap in speed skating, the game won’t allow you to turn forcing you to crash into the wall:

(if the two animations are not in sync, try reloading this page in a new tab or click here)

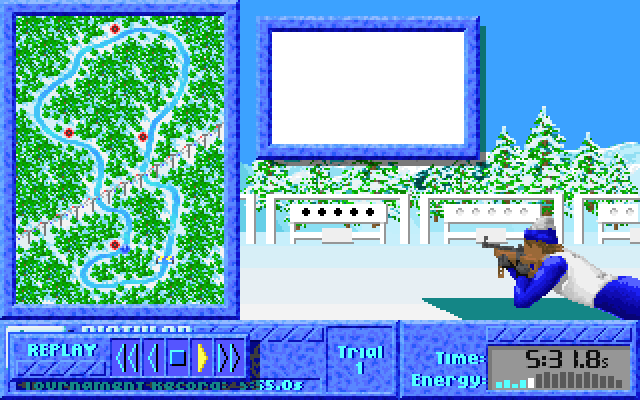

Biathlon

In Biathlon, the copy protection check happens during the shooting sections. If the check fails, it will move your shot by a random amount to the top right, on the second and fourth target in each segment:

(if the two animations are not in sync, try reloading this page in a new tab or click here)

Downhill

The Downhill event also has a copy protection check. It is activated partway into the run, and if it fails it changes the physics behavior to lower the gravity, making you fly off the track:

(if the two animations are not in sync, try reloading this page in a new tab or click here)

Bobsled

The alteration in the Bobsled event is probably the most subtle. When the copy protection check fails, after the first couple of turns, the physics change to give you more drag, slowing you down more than usual:

(if the two animations are not in sync, try reloading this page in a new tab or click here)

Luge

The last of the copy protection checks is the most drastic. During the Luge event, if you are close to the end of the track with a time of below 57.7s, the game just instantly forfeits your run, preventing you from finishing it:

(if the two animations are not in sync, try building a bridge across the peaks of Mt. Kilimanjaro)

Which of the versions handle the hidden copy protection checks correctly?

Now that we know what a failed copy protection check looks like, we can check each of the game versions and cracks we found to see whether they work correctly.

As it turns out, ALL OF THEM, except for one, FAIL THE COPY PROTECTION CHECK! That includes even the official releases: Both the 1996 US release and the 2020 GOG release are broken.

Let’s take a look under the hood of each of them and see what they do

The GOG version (2020)

The GOG version comes with a pre-patched binary, which is based on the installed VGA+EGA fast-load version of the original 1991 release. When looking for what has been changed, beside a couple of padding bytes that do nothing, there are only 2 bytes that are different:

The first is at position 0x12bcdd in the file, which corresponds to offset 0xd47 in overlay 1.

That is the location of the debugger check, and if does the exact same modification we did above ourselves: it changes the jump instruction from a conditional je (0x74) to an unconditional jmp (0xeb), skipping the debugger check.

The other modification is similarly simple and happens at position 0x12bca4 in the file, which corresponds to offset 0xd0e in overlay 1.

This is where the code wheel check is started from, and it replaces the initial cmp opcode (0x83) with a simple retn opcode (0xc3), returning immediately and skipping the code wheel check.

But as we saw, simply skipping the code wheel will trigger the hidden copy protection checks, and the GOG version makes no attempt to circumvent these, causing the game to be broken.

The unknown cracked version

The second of the pre-patched binaries we found, is based on the VGA fast-load version instead.

It has only one meaningfully change compared to the original.

At position 0x122b42, which corresponds to offset 0x406 in overlay 1, it replaces a call instruction with nops (0x90).

That function is the one leading to the code wheel check, so it is very similar to the GOG version, it just skips the function entirely instead of calling it and then immediately returning from it.

The effects are of course also the same: It trips the hidden copy protections and the game behavior is broken.

The “The Humble Guys” crack (1991)

Instead of a pre-patched binary, this crack comes in the form of a program WG.COM which you run separately before the main executable.

It’s only 366 bytes in size, and when we disassemble it we see this (with some unimportant parts omitted):

seg000:010D int3f_interrupt_handler_shim:

seg000:010D cmp ax, 0

seg000:0110 jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:0112 cmp bx, 30h

seg000:0115 jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:0117 cmp cx, 140h

seg000:011B jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:011D cmp dx, 0C8h

seg000:0121 jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:0123 push bp

seg000:0124 mov bp, sp

seg000:0126 push bx

seg000:0127 mov bx, [bp+2]

seg000:012A cmp bx, 0D28h ; check that return address is ovl1:d26 - perform_code_wheel_check call

seg000:012E jnz short loc_10133

seg000:0130 pop bx

seg000:0131 pop bp

seg000:0132 iret

seg000:0133 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:0133 loc_10133:

seg000:0133 pop bx

seg000:0134 pop bp

seg000:0135 exec_original_int3f_handler:

seg000:0135 jmp cs:original_int3f_handler_address

seg000:013A

seg000:013A ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:013A int21_interrupt_handler_shim:

...

seg000:0167 cmp ax, 2B01h ; check for expected value in ax

seg000:016A jnz short exec_original_int21_handler

seg000:016C push bp

seg000:016D mov bp, sp

seg000:016F push bx

seg000:0170 mov bx, [bp+2]

seg000:0173 cmp bx, 0BFBh ; check that return address is ovl2:bf9 - set time interrupt

seg000:0177 jnz short loc_1019C

seg000:0179 push ds

seg000:017A push es

seg000:017B push dx

seg000:017C push ax

seg000:017D mov ax, 353Fh

seg000:0180 int 21h ; Read interrupt vector for int 3fh, so it can be restored afterwards

seg000:0182 mov word ptr cs:original_int3f_handler_address, bx

seg000:0187 mov word ptr cs:original_int3f_handler_address+2, es

seg000:018C mov dx, offset int3f_interrupt_handler_shim

seg000:018F mov bx, cs

seg000:0191 mov ds, bx

seg000:0193 mov ax, 253Fh

seg000:0196 int 21h ; Override int 3fh interrupt handler with our own shim

...

seg000:0218 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:0218 start:

...

seg000:023E push cs

seg000:023F pop ds

seg000:0240 mov bx, 2Ch

seg000:0243 push word ptr [bx]

seg000:0245 pop es

seg000:0246 mov ax, 4900h

seg000:0249 int 21h ; Free memory beyond the program, to allow DOS to use it to load other things into it

seg000:024B mov ax, 3521h

seg000:024E int 21h ; Read interrupt vector for int 21h, so it can be restored afterwards

seg000:0250 mov word ptr cs:original_int21_handler_address, bx

seg000:0255 mov word ptr cs:original_int21_handler_address+2, es

seg000:025A mov dx, offset int21_interrupt_handler_shim

seg000:025D mov ax, 2521h

seg000:0260 int 21h ; Override interrupt vector for int 21h with our own shim

seg000:0262 mov dx, offset aTsrSuccessfull ; Static success message

seg000:0265 mov ah, 9

seg000:0267 int 21h ; Print text to screen

seg000:0269 mov dx, offset aTheGamesWinter ; this is the byte after the interrupt handlers, indicating which bytes need to be preserved

seg000:026C int 27h ; Terminate But Stay Resident - This lets the installed interrupt handlers remain active

The crack works by overriding interrupt handlers and injecting its own code into them.

It first overrides the main DOS interrupt int 21h, and looks for a specific interrupt the game triggers during initialization, at which point it overrides the overlay manager interrupt int 3fh as well.

The reason it needs to do this in two steps is that the int 3fh interrupt is only installed during runtime, so it can only be overridden afterwards.

Why it is looking for that specific random interrupt is beyond me, since there were way more obvious targets, like the interrupt that actually installs the int 3fh handler.

In the overlay manager interrupt, it then looks for one very specific invocation, by checking the register values and return address. That specific invocation happens from offset 0xd26 in overlay 1, where it tries to load and perform the code wheel check. When it finds this interrupt, it will simply skip executing it, effectively skipping the code wheel check.

This has essentially the same effect as the modifications from the pre-patched binaries above. It notably also trips the hidden copy protections and breaks the game.

The Winter+Summer bundle US release (1996)

The official 1996 bundle release came with its own crack in the form of a WINTER.COM loader executable that you run instead of the main binary.

Looking at what it does, we actually see a very similar picture:

seg000:020A int21_interrupt_handler_shim:

seg000:020A push bp

seg000:020B mov bp, sp

seg000:020D cmp word ptr [bp+2], 0BFBh ; check that return address is ovl2:bf9 - set time interrupt

seg000:0212 pop bp

seg000:0213 jnz short exec_original_int21_handler

seg000:0215 push ds

seg000:0216 push es

seg000:0217 push dx

seg000:0218 push ax

seg000:0219 mov ax, 353Fh

seg000:021C int 21h ; Read interrupt vector for int 3fh, so it can be restored afterwards

seg000:021E mov word ptr cs:original_int3f_handler_address, bx

seg000:0223 mov word ptr cs:original_int3f_handler_address+2, es

seg000:0228 mov dx, offset int3f_interrupt_handler_shim

seg000:022B push cs

seg000:022C pop ds

seg000:022D mov ax, 253Fh

seg000:0230 int 21h ; Override int 3fh interrupt handler with our own shim

...

seg000:023D ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:023D int3f_interrupt_handler_shim:

seg000:023D or ax, ax

seg000:023F jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:0241 cmp bx, 30h

seg000:0244 jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:0246 cmp cx, 140h

seg000:024A jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:024C cmp dx, 0C8h

seg000:0250 jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:0252 push bp

seg000:0253 mov bp, sp

seg000:0255 cmp word ptr [bp+2], 0D28h ; check that return address is ovl1:d26 - perform_code_wheel_check call

seg000:025A pop bp

seg000:025B jnz short exec_original_int3f_handler

seg000:025D iret

seg000:025E ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:025E exec_original_int21_handler:

seg000:025E jmp cs:original_int21_handler_address

seg000:0263 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:0263 exec_original_int3f_handler:

seg000:0263 jmp cs:original_int3f_handler_address

...

The opcodes are different, but the check that is performed is exactly the same as the one as in the “The Humble Guys” crack.

It checks the same register state, and it even uses the same weirdly specific int 21h invocation to install the overlay manager shim.

If I were to guess, I’d say someone has taken some “inspiration” from the “The Humble Guys” crack when creating this version. It’s also just shoddily bolted together, with snippets of unused code everywhere. It looks like someone repurposed some other similarly structured crack, and inserted the specifics of the “The Humble Guys” crack into it to make it work for this game.

It of course therefore also has the same problem: it trips the hidden copy protections and the game is broken.

The “Razor1911” crack (1991)

Finally, we get to the only crack that actually works properly. Congratulations to Razor1911 for being the only ones not fooled by the game’s trickery.

Let’s take a look at how their crack works:

seg000:0100 start proc near

seg000:0100 mov sp, 300h

seg000:0103 mov bx, 30h ; '0'

seg000:0106 mov ax, 4A00h

seg000:0109 int 21h ; Free memory beyond the executable

seg000:010B mov ax, 353Fh

seg000:010E int 21h ; Read interrupt vector for int 3fh, so it can be restored afterwards

seg000:0110 mov word ptr original_int3f_handler_address, bx

seg000:0114 mov word ptr original_int3f_handler_address+2, es

seg000:0118 mov ax, 3521h

seg000:011B int 21h ; Read interrupt vector for int 21h, so it can be restored afterwards

seg000:011D mov word ptr original_int21_handler_jump+1, bx

seg000:0121 mov word ptr original_int21_handler_jump+3, es

seg000:0125 push cs

seg000:0126 pop es

seg000:0127 mov ax, 2521h

seg000:012A mov dx, offset int21_interrupt_handler_shim

seg000:012D int 21h ; Override int 21h interrupt handler with our own shim

seg000:012F mov dx, offset aWinterExe ; "WINTER.EXE"

seg000:0132 mov bx, offset parameterBlock

seg000:0135 mov word ptr [bx+4], cs

seg000:0138 mov word ptr [bx+4], cs

seg000:013B mov word ptr [bx+4], cs

seg000:013E mov ax, 4B00h

seg000:0141 int 21h ; Run WINTER.EXE

seg000:0143 mov dx, word ptr original_int21_handler_jump+1

seg000:0147 mov ds, word ptr original_int21_handler_jump+3

seg000:014B mov ax, 2521h

seg000:014E int 21h ; Restore the original int 21h interrupt vector

seg000:0150 push cs

seg000:0151 pop ds

seg000:0152 mov dx, word ptr original_int3f_handler_address

seg000:0156 mov ds, word ptr original_int3f_handler_address+2

seg000:015A mov ax, 253Fh

seg000:015D int 21h ; Restore the original int 3fh interrupt vector

seg000:015F push 0

seg000:0161 retn

seg000:0162 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:0162 int21_interrupt_handler_shim:

seg000:0162 pushf

seg000:0163 cmp ax, 253Fh ; check for game setting up the int 3fh handler

seg000:0166 jnz short loc_10177

seg000:0168 mov word ptr cs:game_int3f_handler_jump+1, dx

seg000:016D mov word ptr cs:game_int3f_handler_jump+3, ds

seg000:0172 push cs

seg000:0173 pop ds

seg000:0174 mov dx, offset int3f_interrupt_handler_shim ; inject our own shim instead of the game's handler

seg000:0177 loc_10177:

seg000:0177 popf

seg000:0178 original_int21_handler_jump:

seg000:0178 jmp far ptr 0:0

seg000:017D ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:017D int3f_interrupt_handler_shim:

seg000:017D push bp

seg000:017E mov bp, sp

seg000:0180 push ax

seg000:0181 push bx

seg000:0182 push cx

seg000:0183 push dx

seg000:0184 push si

seg000:0185 push di

seg000:0186 push ds

seg000:0187 push es

seg000:0188 cmp word ptr [bp+2], 103h ; ovl3:101, skip check for known debuggers

seg000:018D jz short loc_101E0

seg000:018F cmp word ptr [bp+2], 0D4Bh ; ovl1:d49, after failing debugger check, jump to success outcome

seg000:0194 jz short loc_101E7

seg000:0196 cmp word ptr [bp+2], 10Bh ; ovl8:109, skips over code wheel input screen

seg000:019B jz short loc_101D4

seg000:019D cmp word ptr [bp+2], 11Ch ; ovl8:11A, overrides end of code wheel check code adding the hook

seg000:01A2 jz short loc_101AD

seg000:01A4 cmp word ptr [bp+2], 381h ; ovl8:37F, hook added above, set variables to pretend code wheel check succeeded

seg000:01A9 jz short loc_101B9

seg000:01AB jmp short exec_original_overlay_manager

seg000:01AD ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:01AD

seg000:01AD loc_101AD:

seg000:01AD push word ptr [bp+4]

seg000:01B0 pop ds

seg000:01B1 mov word ptr ds:37Fh, 3FCDh

seg000:01B7 jmp short exec_original_overlay_manager

seg000:01B9 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:01B9

seg000:01B9 loc_101B9:

seg000:01B9 mov ax, bx

seg000:01BB xor ax, 0A283h

seg000:01BE mov es:0, ax

seg000:01C2 mov es:2, ax

seg000:01C6 mov es:4, ax

seg000:01CA mov es:8, ax

seg000:01CE mov es:0Ch, ax

seg000:01D2 jmp short skip_original_overlay_manager

seg000:01D4 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:01D4

seg000:01D4 loc_101D4:

seg000:01D4 pop es

seg000:01D5 assume es:nothing

seg000:01D5 pop ds

seg000:01D6 pop di

seg000:01D7 pop si

seg000:01D8 pop dx

seg000:01D9 pop cx

seg000:01DA pop bx

seg000:01DB pop ax

seg000:01DC pop bp

seg000:01DD inc si

seg000:01DE jmp short game_int3f_handler_jump

seg000:01E0 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:01E0

seg000:01E0 loc_101E0:

seg000:01E0 mov word ptr [bp+2], 106h

seg000:01E5 jmp short skip_original_overlay_manager

seg000:01E7 loc_101E7:

seg000:01E7 mov word ptr [bp+2], 0D61h

seg000:01EC jmp short skip_original_overlay_manager

...

The basic mechanism is the same as in the other two cracks: it injects its own code into the int 21h and int 3fh interrupt handlers.

But the logic it performs in the int 3fh shim is slightly more complicated, and makes 5 individual modifications.

The first one skips the check for known debuggers which we looked at before, simply skipping its execution. The second case is for the main anti-debugger check, hooking the interrupt that is called after it is failed and instead skipping over it back to the success case.

The remaining three all deal with the code wheel check.

The third case hooks the interrupt that is called when the code wheel dialog is being opened, and sets si to 1 which will simulate confirming the dialog instantly.

The fourth case is just a helper, it hooks the next interrupt after the dialog is closed, and overrides two bytes at the end of the routine that checks the provided input to inject an artificial int 3f instruction there.

This is not actually a valid overlay interrupt, it is only used as a place for the fifth case to hook into, because there are no other interrupts to hook into in that function.

So finally, the last case is where the code wheel check is actually defeated. It hooks at the end of the input checking routine, after the game has computed the expected result to compare the input against, and it overrides all 5 copies of the ticket number with the correct value the game expects, then pretends the comparison was successful. This way, the code wheel check succeeds, and all the hidden code wheel checks the game will perform later will also work because the correct value has been written everywhere.

With this, the game’s copy protection is completely defeated, with no adverse effects during gameplay.

Side investigation 4 complete!

Help, I have a broken version of the game!

In case you have bought this game from GOG or have one of the many other broken versions out there, I have created a tool to fix the game for you. You can use the tool to patch your binary to remove the hidden copy protection checks (as well as the debugger and code wheel checks themselves in case they are not removed already), so you can enjoy this game without any limitations.

Conclusion - What about creating the perfect ski jump?

My original goal was to deconstruct the game mechanics, specifically for the ski jumping event, but that quest got so thoroughly side-tracked by all the copy protection related investigations that it moved somewhat into the background. Now that the copy protection mysteries are solved, I will be able to focus on that, and it will likely end up being its own write-up. PART 2 IS HERE